The tragic shooting in Buffalo, NY was committed by a man fighting “the great replacement”, a conspiracy theory that has been floating around right wing spaces for the last decade. This conspiracy theory is a modern reskin of “white genocide” conspiracy theories in which a cabal of Jews in some way or another is responsible for attempting to destroy the white race through the exploitation of people of color. These theories have been around for over a century and should only be understood as white supremacy.

Why am I talking about this? Well, the classics are heavily tied into these conspiracy theories. The right uses antiquity as a cudgel to lie about the present. Most obviously to the case referenced earlier, the book popularizing the modern version of the great replacement theory relies heavily on arguments based on Plato’s writings, which have been thoroughly debunked here. However, this is by no means the first way in which classics have been used to prop up racism. Consider the fall of the Roman Empire, as written about by famous historian Tenney Frank. In Frank’s influential writings, the fall of Rome is caused by the influx of non-Romans whose racial mixture diluted the energy of the Roman people. While this belief that foreigners were responsible for Rome’s downfall has existed even since Rome itself, Frank used the field of epigraphy, the study of inscriptions on Roman buildings and tombstones, to give a more academic sheen to his theories which continues to be parroted by the right wing even today. Similarly, consider how Seneca, a famous Roman stoic philosopher, was read extensively by antebellum slave owners when creating justifications for their own slavery.

These roots haven’t disappeared either. In fact, last year I went into office hours with the wonderful Professor Weintritt about a very peculiar trend I kept noticing in the writings of modern classics papers. Some modern authors have a very odd habit of minimizing Roman slavery and comparing Roman slavery favorably to American chattel slavery, and claiming it was not so bad. My instinct was that this was ridiculous, and during my final quarter of college I had the amazing opportunity to study this instinct through an independent study with Professor Weintritt on the historiography of Roman slavery. In this post I hope to share what I learned. Firstly, the classics as a field is in a tumultuous place, with huge changes in methodologies and approaches being made, partly in response to critiques which threaten the classics departments themselves. Secondly, Roman slavery was truly terrible, but due to the slowness of academia, classics students might still be reading introductory work written before this academic consensus. Lastly, I have realized the importance of the classics, and that their part in our cultural mythology which would be catastrophic to surrender to the right.

Should the classics drink the hemlock?

One of my earliest questions when I started this project was, “why do classics departments exist?” If I wanted to study the history of English colonialism for instance, I would take a class in the history department. Similarly, if I wanted to study Shakespeare, I would look into a literature department. On the other hand, history, philosophy, and poetry are all in the same department when it comes to anything relevant to the ancient Mediterranean. It turns out there are a few reasons for this. Firstly, a historical reason: classics was seen as an essential part of an education for centuries and used to be required. During the Renaissance, Greece and Rome were seen as legendary, and study of them as the basis for an education came into fashion. In fact, until 1960 every graduating student at Oxford was expected to have a grasp of Greek and Latin. As I will get into later, academia is slow, and while these requirements don’t exist anymore, if you are putting the Greeks and Romans on this pedestal and requiring every student to study it, there is a logic in grouping it all into a department. It is certainly all tied together. The second, and more legitimate reason in my eyes is that it fosters interdisciplinary expertise and collaboration. There is a lot of focus in the works I read for this project on ways literature could be used in understanding history, and plenty of work looks at the inverse as well. Epigraphy, archeology, philosophy and drama are all tied together in our understanding of the ancient Mediterranean. By maintaining a single department these different foci and specialties mingle and come together in ways that might be difficult if the classics were broken up.

However, one of the most famous people in the field thinks classics should potentially be dissolved into other departments if it can’t reckon with its history of white supremacy. Dan-el Padilla Peralta is a famous classicist who argues that the modern conception of whiteness is rooted in the classics. This is certainly not unfounded. This fantastic deep dive by the New York Times spotlights Peralta’s view on how classics perpetuates and produces racism. Frank comes to mind for how this happens, but the process in Peralta’s eyes clearly continues today. Moreover, the existence of the classics is a statement about what things from ancient society we see as important and as the lineage to our society. It draws its roots from Renaissance priorities about what they thought was best, and, from Peralta’s point of view, until it completely separates itself from those roots, its existence is a testament to those problematic ideals.

The problems run deep, and as I previously mentioned, I saw the problem in works that would make comparisons between American and Roman slavery to minimize the severity of the experience of enslaved peoples. For instance, one piece, which to its credit does describe some of the horrors of Roman slavery, goes out of its way to compare the experience of unions between enslaved people to the American period for no particular reason other than to point out how keeping slaves in families together was a privilege that most Roman slaves seemed to have. Obviously, this wasn’t about the happiness of enslaved people but rather to incentivize reproduction to maintain the slave population. Why did this author make this decision? I found this quite troubling, and wondered why if there is a movement from people like Peralta, why is it not quickly becoming the dominant narrative?

Achilles and dogmatic drag: the Zeno paradox

The thing is, regardless of the comparison, as became obvious over the course of the independent study, Roman slavery was horrific. There were certainly some differences between American and Roman slavery that are worth noting. For instance, there wasn’t a racial element in the modern sense of the word in ancient Roman slavery. While slaves often were captured in war, they weren’t representing any one particular skin color, and importance wasn’t placed on the racial groups we have today. Another difference was manumission, a relatively common occurrence in Rome in which some slaves were granted citizenship by their owners and integrated into society. Additionally, some slaves were given quite a few privileges. However, in 1983, Moses Finley, a seminal classicist, wrote “Ancient Slavery Modern Ideology” which, while acknowledging these aspects of Roman slavery, went on to become a central work in modern scholarship. In particular I want to highlight his third chapter which made an extensive effort to demonstrate that the institution of slavery in Rome was extremely widespread and fundamentally inhumane; full of assault, sexual violence, and human suffering which should not be made light of.

So if the scholarship exists, why did I see modern papers that didn’t reckon with it? There are a few factors in favor of these scholars. Notably, the sources which exist can disguise the problem. There aren’t any quality accounts of slavery by the enslaved themselves. We lack diaries or an oral history that could allow the enslaved people to speak for themselves. Even Finley admits he sees no way to uncover the enslaved perspective given the lack of sources from them. This is compounded by the fact that the vast majority of sources were written by the wealthy and powerful who often owned slaves. These sources tend to disproportionately talk about manumission and downplay the severity of slavery. This may play a part in uninformed scholars’ works.

However, the most impactful factor which we recognized as a cause of this ongoing failure was “dogmatic drag”. This is a phrase to describe how long it takes status quo views to shift in academia and the larger world. To explain, consider that one of my routine surprises in the project was hearing how long things take in academia. For instance, a few weeks ago, Professor Weintritt visited a conference and told me about a few new interesting classics projects getting started. She said one of them in the very early phases might not publish a book for a decade! If this is the speed that new ideas take to get published and be fully introduced to the world, it is easy to imagine why new understandings of old established scholarship can be slow to propagate. Even after the books come out, it can take time for the ideas to worm themselves out into the world, first having to be read and understood by various scholars across academia. At that point it can start to be included in new works and trickle down into readings for classes each of which might take even longer. Some of those students will go on to be professors and begin to teach those new ideas, but until the old batch of professors retire the older dogma might continue to be taught.

Throughout this process, there are various roadblocks which might slow things down even more. There may be cultural factors which cause problems. For instance, sourcebooks are very important in classics. These books will have the Latin and English translations of various sources along with short notes providing a bit of context. These books are excellent for finding potential primary sources. However, writing new ones hasn’t been in vogue for decades. Accordingly, the ones students continue to use today were often written in the 1900s. It is not surprising that some of these books do not use Finley’s analysis of slavery in their contextual details, and give a very favorable review of defenders of Roman slavery such as Seneca. For instance, in a sourcebook on Seneca’s writings, in the intro to a piece about slavery, the author claims that a piece is showing a “credible humanitarianism” in Seneca. On the other hand modern scholars argue the same piece was in service solely to slave owners’ welfare, and used to defend antebellum slavery. Until the books which teachers give to students are rewritten and re-contextualized, this misinformation will continue to be spread.

Similarly, writing an idea that challenges dogma is more difficult than one which agrees with it, requiring more time. Writing something that goes in line with the status quo can use similar sources as previous popular work, and rely on it for a narrative to piece the evidence together. On the other hand, a significantly new piece requires new well thought-out ideas and new sources to support them. Peralta, the aforementioned prominent classicist who thinks the classics should potentially be disbanded, wrote a piece in 2017 which aims to use a new methodology to try to write enslaved people back into the narrative and learn about their experience. He does this by attempting to analyze antebellum slave religion to provide insight on slave religion of ancient Rome. In this piece Peralta’s writing is belabored by caveats and a prevent defense attitude: he attempts to justify and rejustify every small claim because he is making bold claims that require defense. While I agree with this decision, it certainly must have cost him far more hours than a piece which didn’t need to have nearly 11 full pages of single space citations.

In order to understand the significance of Peralta’s piece it is worth discussing how previous scholars used comparative examples in the study of ancient slavery. Older scholars like Finley used comparisons to make claims about what was possible or impossible. For instance, Finley would note how there were few slave rebellions in America but American slavery was inhumane, therefore we shouldn’t interpret a dearth of slave rebellions in Rome as a sign that slavery wasn’t bad. On the other Peralta, is doing his part to improve classics by trying to use slave religious experiences in America to try to inform us what Roman slave religion might have included rather than simply discounting impossibilities. Peralta’s method isn’t as clearly sound a way to provide evidence for something as Finley’s, as it isn’t always clear how enslaved experiences millennia apart would be necessarily similar in something like religion, but it does have the potential to bring something new.

Peralta isn’t alone in trying to find new ways to understand the enslaved experience despite a lack of sources either. Several works Professor Weintritt and I analyzed used new methodological techniques to fill this gap. For instance, Jackie Murray, a classicist, has an upcoming book which analyzes the descriptions in the Odyssey to see how monster descriptions for instance could be used to understand Roman bigotry. Another author, Amy Richlin, tried to read between the lines in the works of Plautus to understand the perspective of enslaved people who often were involved in the production of theater. Furthermore, Professor Weintritt told me about pieces still early in development. For instance, Joseph Howley is working on a piece about the role of enslaved people in taking down dictations from Roman authors which was the preferred form of writing. This meant when the author says “you” in reference to the audience he is directly addressing a slave, potentially giving insight into the dynamic between them.

At first this all seemed a bit dodgy to me. After all, Peralta admits that there is room for skepticism in his paper. Eventually I came around, in that, while I don’t necessarily understand or agree with all of these techniques, it is the role of academia to try things and see what works. The quality stuff will rise to the top and hopefully change the narrative. I am confident that experimentation is a key part of that, and some experiments might not work, but there is nothing wrong with trying. Moreover this gives me a lot of hope for the future of classics. There are plenty of people doing new work, some of which will eventually have a big impact on classics departments. Similarly, dogmatic drag can only be solved through more work. Newer source books, conferences, and more academic work will make a difference over time.

We need an apotheosis of classics

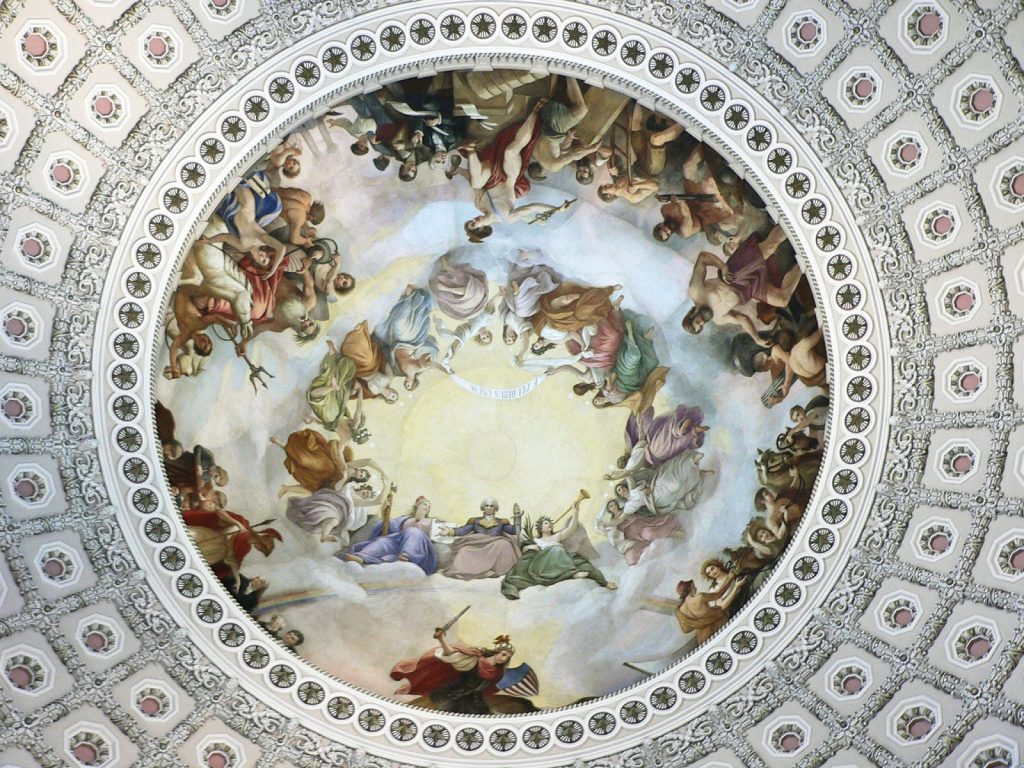

I’ve always found the classics powerful. Maybe my first exposure was when my parents read me D’Aulaires books of Norse and Greek Myths as a child, which I still remember fondly. I got into Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson young adult fiction series, which sets the Greek gods in modern times, at a young age, and that introduced me to a fundamentally different model of mythology. While it had supernatural elements, it also posited that antiquity is still alive today, even beyond the fantastical demigods and monsters. It is why our most important buildings have marble columns and the Federalist Papers were written under the pen name “Publius”. The actual history of Greece and Rome are an important part of modern day mythology explaining how and why we came to be. Moreover, they continue to act as important tools for how we frame our thoughts about the world.

In my eyes, this is the role of myths in a society. They are cultural touchstones which we use to communicate our thoughts and ideas about the world. We come back to them because of the cultural power they have over us. Importantly, when I say myths in this case I don’t exclusively mean the stuff in D’Aulaires books, although they are powerful. I also mean the stories we continue to pass on from Rome. The rise and fall of Caesar or the death of Socrates. These stories and symbols hold value. That is why Frank found power in explaining racism through the fall of Rome and why the “Great Replacement” bases its arguments in Plato. It is why neo-Nazis continue to use pagan symbols, and talk about ancient Rome. It’s also why we love the Hamilton musical and why Biden keeps comparing himself to FDR. All the stories we tell make a cultural quilt with various elements that we can rely on to communicate and convince others.

Therefore if we want to fight back against the right using these stories we can’t just give them up and try to ignore them. We need to use these stories to our advantage. For instance, FDR wasn’t perfect and everyone knows it. However, it is very wise of Biden to bring him up despite the internment camps (among other problematic decisions). If Biden can tell a convincing story about the best of FDR and use it to pass important legislation then it is worth it because it will help people today. This isn’t to oppose him recognizing the flaws, and making statements about the racist treatment of Japanese Americans during WWII but rather to support him in his continued efforts to cast our culture through a favorable lens to achieve our political goals. For instance, George Washington was a slave owner and Lincoln was responsible for many Native American deaths. These were both morally reprehensible. However, in a country where Washington and Lincoln have higher approval ratings than any Democrat today could dream of, it is to our benefit to not reject these mythological figures. Washington and Lincoln more than anything were for the union. Can you imagine Washington ignoring an insurrection on the capitol building? Lincoln was an institutionalist who would be disgusted by the continued attacks by the right on American institutions. We can’t allow Republicans to claim to be the party of patriotism and our founders and also be the party of opposing democracy. These figures had virtues that we respect and it is important not to abandon them.

In the same way classics are not something we should surrender just because fascists identify with them. There are several ways we can try to do this. For instance, we could offload this role to academics. I am a big fan of Pharos, a group of academics who publish refutations of alt-right claims about the classics regularly. They do a great job of laying out what is actually true, and how Rome is used erroneously for the right’s myth making. However, the biggest problem with Pharos is they have no style. They are scholars, and carry that baggage through their tone and presentation. It should not be surprising that most people wouldn’t find them particularly interesting to read. Scholars in general are very good at producing work to refute and complicate topics. However, they often lack the pizzazz needed to sell the work to a general audience.

The larger problem with this method is that it doesn’t provide any counter-narrative. There is no alternative myth making done by the scholars in a more left wing sense, just a debunking of politically problematic myths. I am not sure scholars are equipped to do this. It goes against what they are trained to do. Narratives on some level simplify history and academics complicate it, putting academics at odds with the mission I am proposing. Instead, it is my belief that it is the role of politicians, thought-leaders, and artists to take these facts and weave a convincing narrative using the important shared touchstone that is Rome. We should highlight that antiquity had some of the earliest experiments with more democratic forms of government. We can be proud of the steps Athens took, even if the freedoms weren’t shared by everyone in the city. Similarly, we can weave a narrative about the history of social movements. Rome had some of the first general strikes, which guaranteed more political power to the lower classes. Few know that arguably the first women’s march was in Rome, over bodily autonomy no less! Lastly, more and more scholarship has been focusing on the multiculturalism of Rome. As Rome grew it took over many places and integrated disparate peoples often adopting aspects of their various cultures. It was a remarkable way to run an empire that we can and should talk about as the roots of American multiculturalism.

How can we turn our back on this? As this work continues to be taught at the college level, it will trickle down to the cultural producers of tomorrow. Authors, youtubers, and more will know about it and use it to inform their works! We should not reject it solely on account of what made it problematic. Rather, just like in the case I made for embracing American history, we can and should find what about Rome is useful to us today and embrace it wholeheartedly.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.